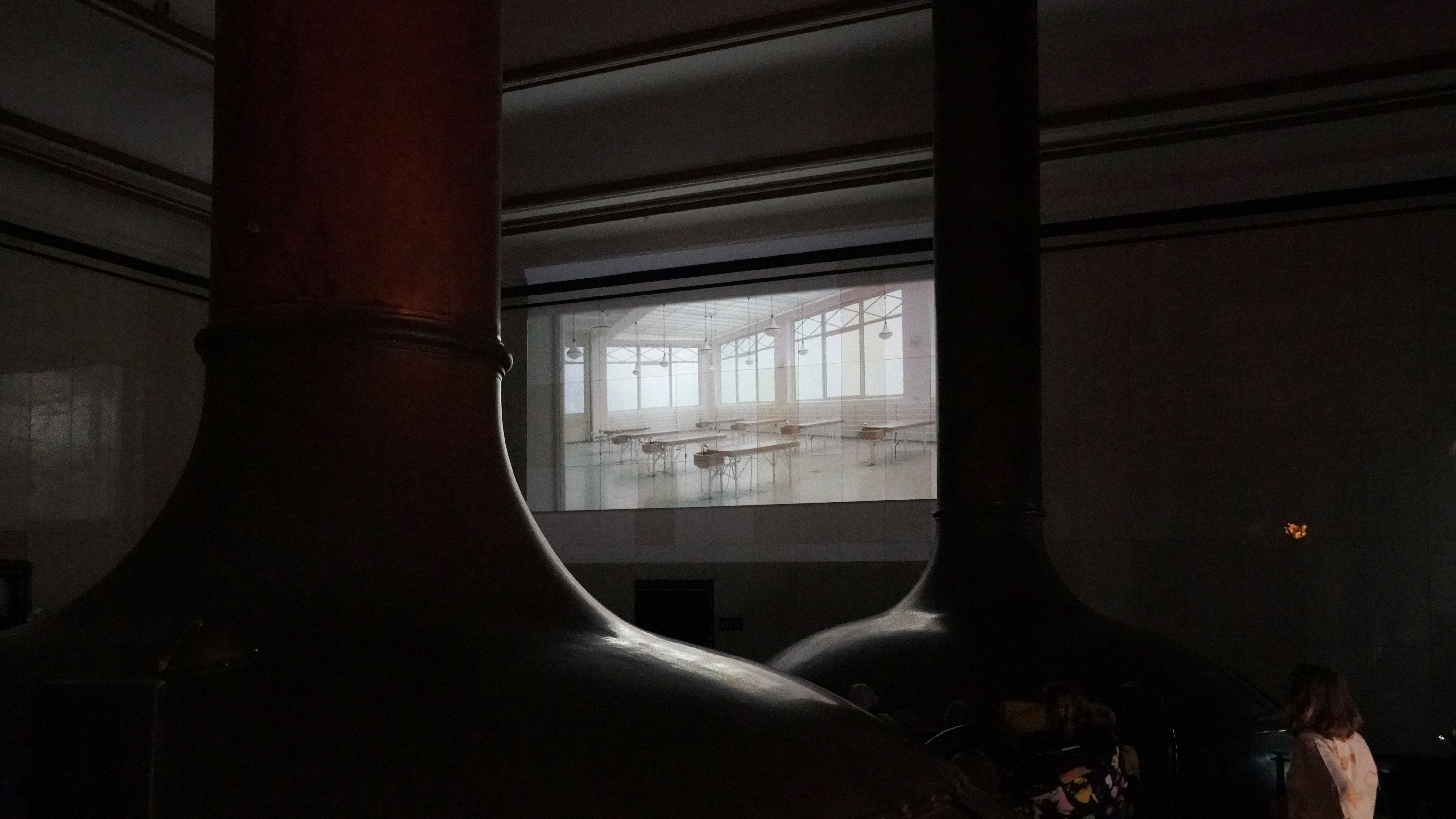

touching fine lines, 2024, 1-2 channel video, 11:50 min, cinescope, video stills and images from exhibition premiere at Bar Babette at the KINDL Sudhaus, Berlin

–

This video installation is a portrait of the Autopsy Hall at the Medical History Museum in Hamburg. Built in 1927 and restored to its original form, this room now is a museum piece. Thereby, this emotionally loaded space on the afterlife of bodies has turned from a place of working with your hands to a place in which touch is prohibited.

Continuing this idea of “opening” or “touching” a body physically and emotionally, this video investigates the materialities of the room next to the immaterial atmosphere channeled by the light-focused architecture.

Filmed via body cameras and floating shots, mixed with original audio recordings of the room’s ventilation system combined with a singing voice, the split screen projection explores liminal spaces and the politics around touch(-ing border lines).

—

Director & performer: Kirstin Burckhardt

Director of Photography: Max Hilsamer

Editor: Max Hilsamer and Kirstin Burckhardt

Music: Tobias Gronau

Voice mastering: Mario Asef

Color correction: Kevin Kopacka

First Assistant Director: Jessica Owusu Boakye

“touching fine lines” is a two part project consisting of this video and the book “Brutal with Love” in collaboration with Lisa W Carlson, published at Vexer.

—

The project was enabled through the kind support of:

the Ministry for Culture and Media Hamburg

Hamburgische Kulturstiftung

Rudolf Augstein Stiftung

IASPIS Sweden

Text about “touching fine lines” in the book “Brutal with Love”:

The first time I touched the autopsy tables was in secret. I was alone in the autopsy hall which is now an exhibition piece of the Museum for Medical History Hamburg after being used for science and education from 1927-2006/08. Thus, “touching” already equaled “crossing” the invisible fine line in this museum context.

—

The table’s surface was colder than I had expected, and the cold made the room real. It contrasted the ethereal, almost sublime air of the space, bathed in a soft hue of light from the milky windowpanes looming large at the side and ceiling. My fingers were immediately drawn to the groves in the table’s surface. How much muscle force would you need to incise so deeply – through bone into stone? Knowing that this was a place of work. Hard working hands, cutting into body surfaces, I was gently exploring the traces of this materialized history, trying to read like Braille what had been alive before.

—

Yet it did feel logical, even necessary, to use the body as an entry point if one wanted to grasp the undeniable impact of the room upon entering and moving within it. As a body-based visual artist and psychologist I wanted to know: How can we deal with heavily charged spaces? Especially an emotionally and historically charged body-related room, such as the autopsy hall, if not in a body-based approach like performance art? Coming from a scientific perspective from my psychology degree I was curious how a quantitative approach might extend to this artistic practice and bridge a dialogue to the research already conducted at the autopsy hall, which is connected to the Institute for the History and Ethics of Medicine.

—

Upon entering the room I knew I wanted to do a site-specific performative piece. In 2018, I was honored to be part of the interdisciplinary symposium “Material Cultures of Psychiatry”, organized by the then in-house curator and researcher at the Museum, Dr. Monika Ankele, together with Benoît Majerus. The planned performance in the autopsy hall could not take place, because of differing opinions (the performance included touching the tables), but we, a group of seven performers, developed an intervention in the space instead, using our voices.

—

What separates the living from the dead body is the ability to voice. We lack their first person-perspective, their self-chosen representation, so we post-create narratives. We can try to tell or protect their stories, but it is only our voices that ultimately can be heard. How can we be sensitive translators? I remember being in the autopsy hall, alone. I pricked my ears to listen to the naked sounds. Most vividly I could hear a sinus tone whistling through the industrious pipes like a large lung. Taking a receiving breath, I heard my voice injected in the room, serpentine around the sinus tune. The echo of the room, 10 seconds, allowed me to add layers. Voice lingering, floating, and evaporating at different speeds. The layers become a body that could not be dissected into parts yet made a plurality audible.

—

I wanted to continue this exploration with the voice, especially after meeting four other wonderful voice-working artist and visited the autopsy hall with one of them for on-site research, but then that the pandemic hit, and all plans had to change radically. I was devastated but determined to continue this piece so close to the confrontation with death, science, and the (in-)ability to touch. If the people could not come to the room, I would bring it to them. Choosing to re-think the project as a two-part-piece with a video (titled “touching fine lines”) and a book (titled “Brutal with Love”) allowed the project to “survive the pandemic” and I am very grateful to the funding partners (Ministry for Culture and Media Hamburg, Hamburgische Kulturstiftung, Rudolf Augstein Foundation, and IASPIS) for supporting this change. Situating our work in the pandemic process, Lisa and I wrote recently: “The Covid-19 pandemic has affected every society and every person. It has reminded us that we are connected on a global level and the importance of physical proximity. We are two artists who have developed a strong professional relationship and a deep friendship in which we have created trust in each other and have dared to express difficult feelings and questions. The pandemic has confronted us with existential subjects, with death, with fragility, and at the same time with what we want to hold close and dear: The feeling of being alive, of flourishing, of being filled with love for others”.

—

Under strict Covid regulations I shot the video “touching fine lines” with a tiny team. We contrasted a camera on a rig (“flying” through the room like a “bodiless body”) with a gimbal-held camera, and third camera in front of my eyes to embody a first person-perspective. Working from body-based research meant to me: walking my body into the space, hearing the hall witness my steps by its echo back, watching the hair on my skin slightly rise upon touching the chilling stone beds, tracing the groves in these hard surfaces, acknowledging the force it takes to chip this hardness, thus listening, moving, and listening again.

Comments are closed.